About the Gag Laws

By Nina Funnell

What are the gag-laws and why are they a problem?

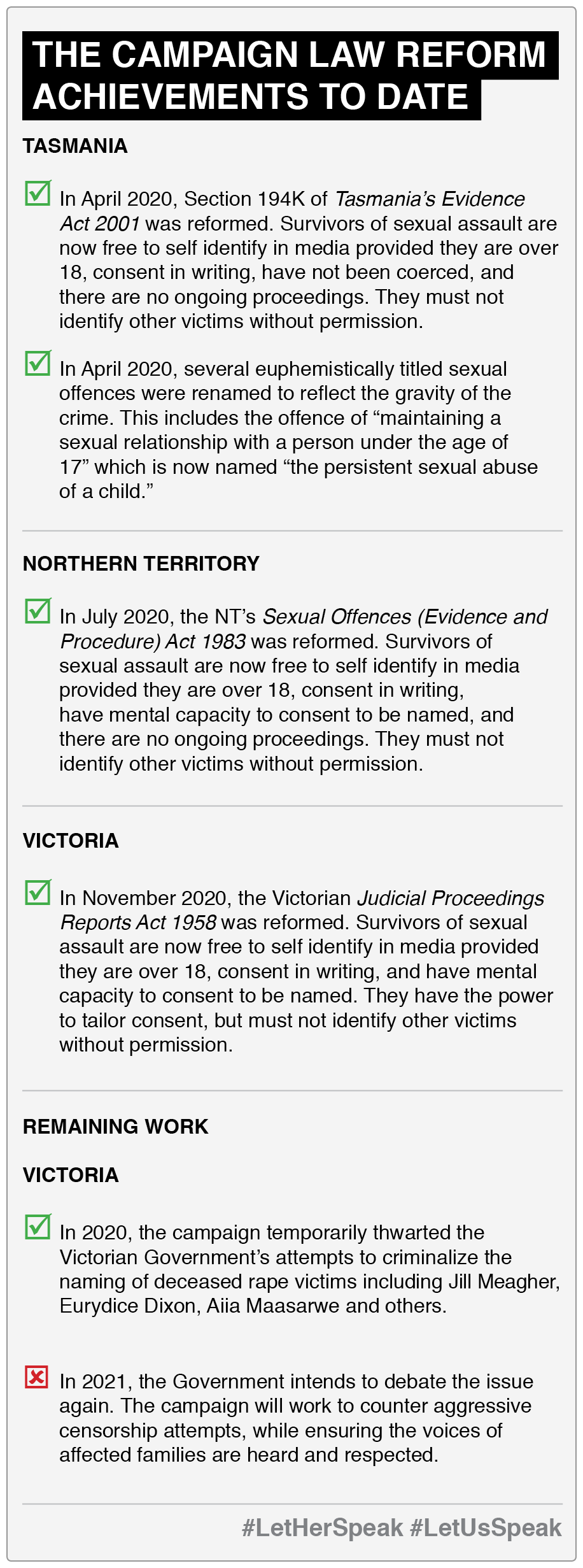

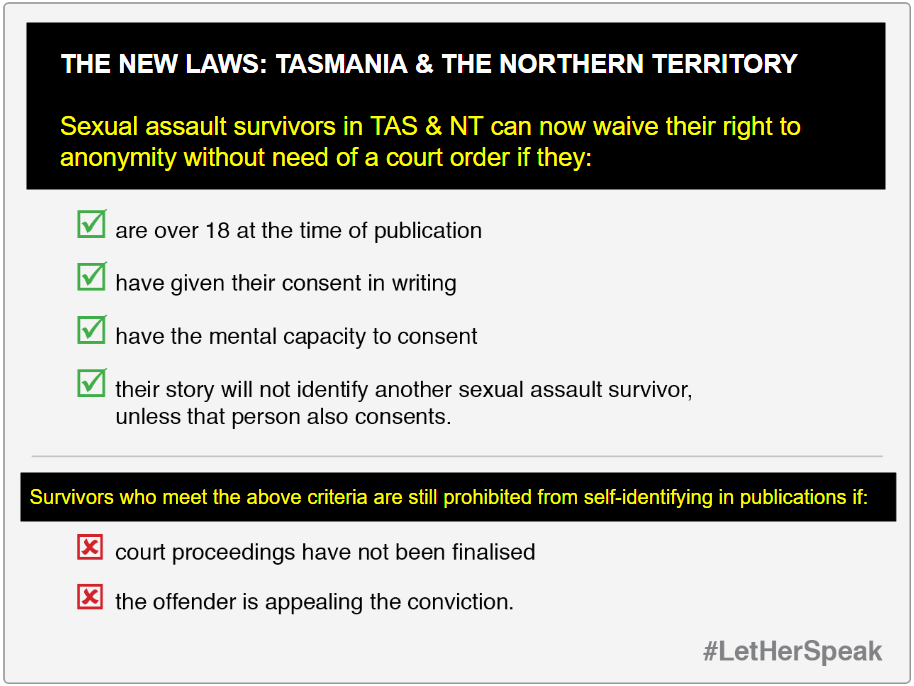

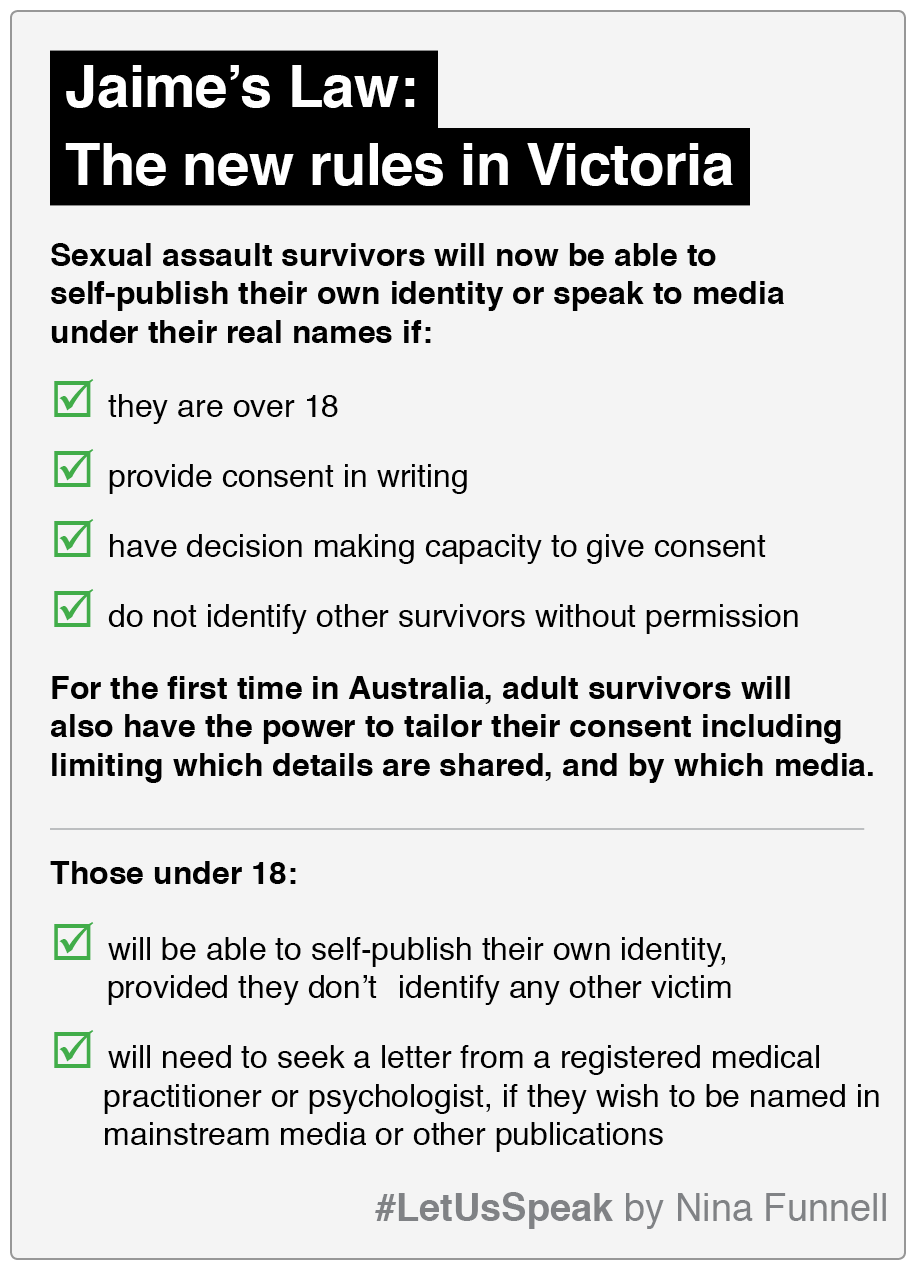

Sexual assault victim gag-laws have existed in Australia for many decades. In 2018, the #LetHerSpeak/ #LetUsSpeak campaign was launched to reform these laws.

Initially intended to protect survivors from media exploitation, the victim gag-laws have had several unintended consequences including:

- silencing individual survivors who wish to speak out publicly, thereby increasing their sense of isolation, powerlessness and voicelessness;

- exacerbating existing trauma, through the further removal of control and denial of personal agency;

- maintaining and increasing social stigma around sexual violence by keeping taboos intact;

- enabling and protecting offenders of these crimes by ‘muzzling’ the victims even after convictions are in place;

- disempowering sexual assault survivors in the community more broadly, by erasing from view public survivor role models;

- restricting survivor-led advocacy and education by placing conditions on how survivors can participate and be heard in public debates – including those debates which directly affect them.

More broadly, victim gag-laws also have flow-on negative effects for the community at large.

That is, by silencing survivors and removing their experiences from view, gag-laws also obscure opportunities for the public to learn from survivors and better understand sexual violence, its causes and its impacts.

While many sexual assault survivors may not wish to waive their right to anonymity – and this should always remain their choice – for those who do, speaking out can hold many benefits to both themselves and the wider community.

From an individual perspective, choosing to speak out about one’s own experience can be an important and potentially therapeutic form of healing and recovery, as it allows the survivor to reclaim ownership and control over their own narrative.

More broadly, speaking out can also serve the public interest, and many public survivors have played an important role in shaping community attitudes, beliefs and understanding of sexual violence.

Beyond that, survivor voices can also contribute to structural and policy reform. In recent years, survivor-led public advocacy has directly prompted multiple inquiries and Commissions into the prevalence of sexual violence and institutional responses to it. This work, in turn, helps to prevent sexual violence from occurring in the first place. Other general benefits include:

- raising awareness about the prevalence of violence in the community;

- educating the public on the impacts of sexual violence;

- highlighting the need for more effective prevention and response strategies;

- challenging stigma and silence connected with sexual violence;

- breaking down the social isolation experienced by other individual victim- survivors in the community;

- empowering other survivors to engage in help seeking behaviour.

What were the potential punishments for breaking the gag-laws?

Potential punishments for breaking the law have historically included jail time or heavy fines. For example, in the Northern Territory survivors (or individual journalists) could face up to six months jail for breaking the gag law (in some cases this can still occur and our work continues).

In Victoria, the punishment for breaking the gag law was a fine and/ or up to four months jail.

In 2012, a Tasmanian media outlet was prosecuted and fined $20,000 for naming a survivor who was over 18 and fully consented to be named, demonstrating that the laws were not ‘on the books only’.

https://www.austlii.edu.au/

Why not simply apply to be exempted from the gag-laws?

Marque Lawyers, the campaign’s legal partner has now secured over a dozen court orders on behalf of individual sexual assault survivors who have been impacted by gag-laws in Tasmania, the NT and Victoria. While the campaign team are very proud to have been able to provide this direct support, we have observed that the process of applying for court orders has proved stressful and re-traumatising for many of those survivors who we have supported. In particular, we have observed that the process:

- can exacerbate underlying trauma by further stripping the survivor of agency and control over their own story and voice;

- subjects the victim-survivor to an additional legal process which may be triggering given past court experiences;

- is time consuming and costly. Even in cases where law firms are willing to act in a pro-bono capacity there can be additional out of pocket expenses for each survivor (such as time off work to attend hearings etc).

More broadly, it is not sustainable to have a small donation-reliant campaign perform this work and in the past, survivors who have not been able to afford their own legal and court costs have often turned to media outlets to perform that legal work. That then creates an additional problem as it puts the survivor at the ‘mercy’ of the media outlet who may then expect or demand exclusivity. This again removes power and control from the survivor while recreating power imbalances again.

There are also different barriers to access for different survivors and we note that compounding disadvantage can make some survivors far less likely to be able to seek or access support which may be provided from legal services such as Legal Aid.

Ultimately, the situation has been entirely untenable and unsustainable. As we have known and argued from the beginning, the only long term answer is law reform.

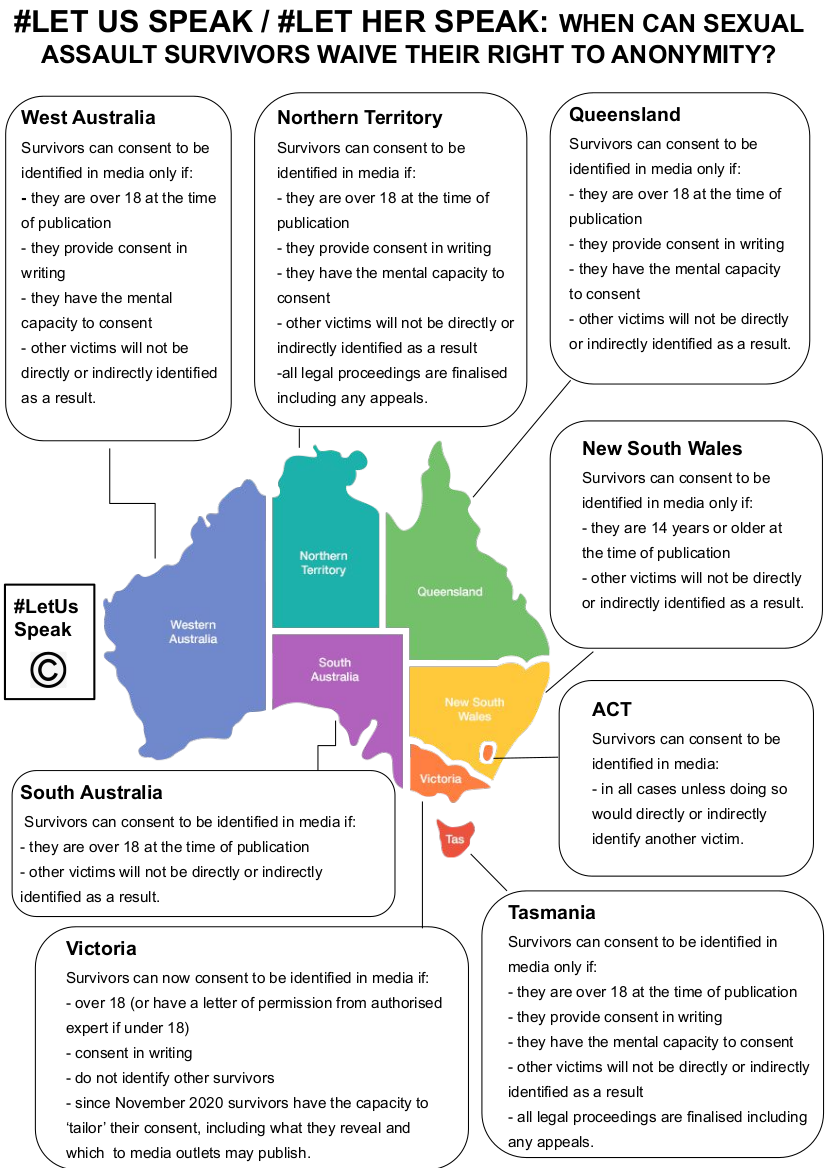

Want to learn more? Laws by Jurisdiction:

We’ve briefly summarised the laws by jurisdiction in the map below, but to learn more about laws in your jurisdiction, you can access the legislation via the links here:

WA http://www8.austlii.edu.au/

NT https://legislation.nt.gov.au/

QLD http://classic.austlii.edu.au/

NSW http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/

ACT http://www6.austlii.edu.au/

TAS http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/

VIC http://classic.austlii.edu.au/

SA http://classic.austlii.edu.au/