Why we advocate

By Nina Funnell

In 2017, I met Tasmanian sexual assault survivor Grace Tame and began working on her story with a view to publishing. As a journalist, I’d spent years reporting on sexual violence, and yet – being based in NSW – I had never heard of sexual assault victim gag-laws.

So when News.com.au Senior Legal Counsel, Gina McWilliams informed me of the effect of Section 194K of the Tasmanian Evidence Act 2001, I was shocked.

As an investigative reporter I found it a clearly regressive law which compromised several important principles connected with public interest journalism and press freedom.

But as a survivor myself, I was appalled. At age 23, I’d gone public with my own story of sexual assault and that decision had been a turning point in my own healing and recovery: it was the moment I began to reclaim ownership and control over an event in my life where I had been fundamentally stripped of all control.

It was also the moment I let my offender and the world know that I was not defined through his actions and choices, but through my own path to recovery.

Of course many survivors may choose never to waive their right to anonymity. This must always be respected and more work is needed to critically examine and address the barriers which make speaking out so difficult, particularly to more marginalised groups of survivors.

But for those of us who do want to speak out, being able to make that choice in our own time, on our own terms can be healing, therapeutic and restorative.

Not just to individual survivors themselves, but also to the wider community: when survivors are able to publicly identify themselves they can play a key role in educating others and positively shifting community attitudes and beliefs. They often motivate other survivors to access support, and through survivor-led advocacy, many inquiries, Commissions, and public reviews have been triggered. This in turn can lead to interventions which ultimately prevent violence from occurring in the first place.

Despite these benefits, the gag-laws still prohibited journalists from naming survivors who wished to be named. Worse, survivors themselves were actively risking prosecution if they broke the law.

Criminalizing those who had already been substantially wronged was obviously outrageous. So too was the suggestion that survivors should have to go back to court – at their own expense and inconvenience – to apply for court orders to be exempted from the gag-law.

But I was also troubled by the paternalistic assumption that survivors cannot be trusted to make informed choices about their own stories and who they share them with. While this is a sensitive area of media law and certain protections are absolutely warranted, there seemed to be something deeply infantilizing and un-nuanced about a blanket ban on all survivors speaking, especially since it also would prohibit autobiographies and other forms of self-expression.

As I reflected on my own experience of ‘going public’, I realised that had my assault happened in Hobart (instead of Sydney), I would not have been able to speak out as I had.

By this stage Gina McWilliams had offered to obtain a court order on Grace’s behalf so that I could report her story and Grace had accepted the offer. But as I turned the problem over in my mind, I came to realise that was a short term solution to a much more systemic problem.

The only sustainable solution was law reform.

And so the #LetHerSpeak campaign was born.

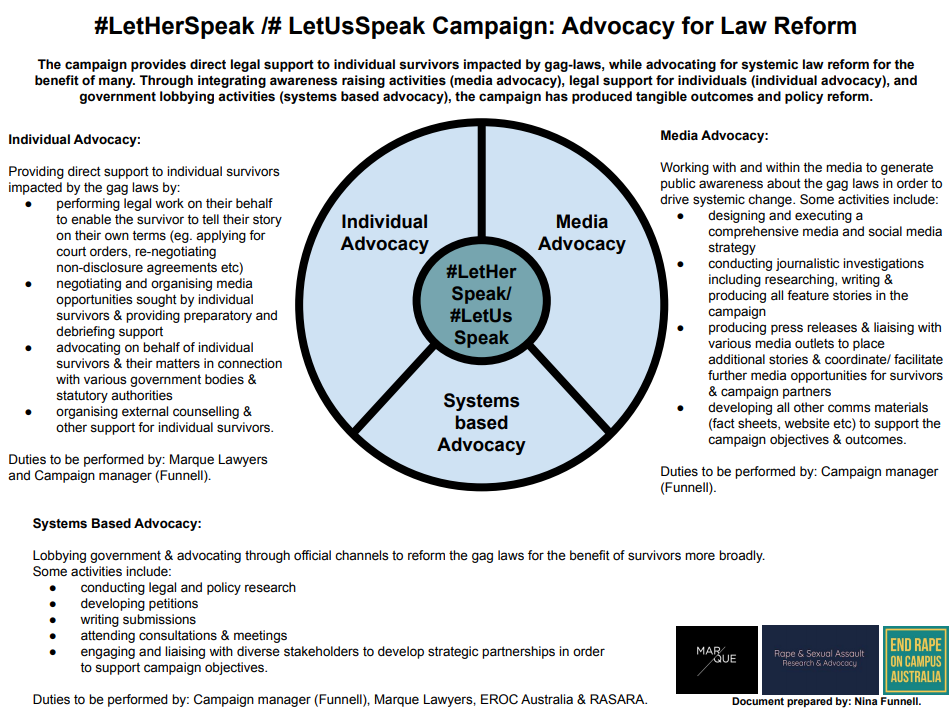

Working closely with the News.com.au and the founding campaign partners (End Rape On Campus Australia and Marque Lawyers) I designed and created the campaign. The original strategic plan (including all legal and policy research, the media strategy, the social media roll out plan, the petition, and all other assets and reporting materials) took over three months to design and create. On November 8, 2018, I formally launched the campaign along with all the partner organisations.

Since then the campaign has grown and evolved. We’ve now had the privilege of providing direct legal assistance to 17 individual survivors across three jurisdictions and the campaign has led to 4 law reforms to date. The campaign has also received numerous media accolades including two Walkley awards, a Kennedy award, a MEAA NT Media award, among others.

But by far the most important thing has been restoring agency, dignity and voice to the individual survivors in the campaign.

It has been a tremendous privilege to be entrusted with the responsibility of performing this work and I am grateful to every person who has worked on this campaign and every survivor who joined with us.

To all survivors: I believe you. It’s not your fault. You’re not alone. Your voice matters.

– Nina Funnell, #LetHerSpeak / #LetUsSpeak campaign creator and manager